Why "Having It All" Is a Myth—and an Economist’s Guide to What to Aim for Instead

Dr. Corinne Low on why women are still getting the short end of the stick—and what we can do about it.

Prepping for your own busy fall? Start with bestsellers from M.M.LaFleur.

For years, economist Corinne Low studied the trade-offs facing working mothers—until 2017, when she became one. Suddenly, she saw her research and her personal life dovetailing, pumping breast milk in Amtrak bathrooms during her two-and-a-half-hour commute from New York to Philadelphia, caught in what felt like an impossible bind. But instead of accepting failure, she did what any good math nerd would do: looked at the numbers. Her discovery? In Corinne’s own words: “It’s not in your head, it’s in the data.”

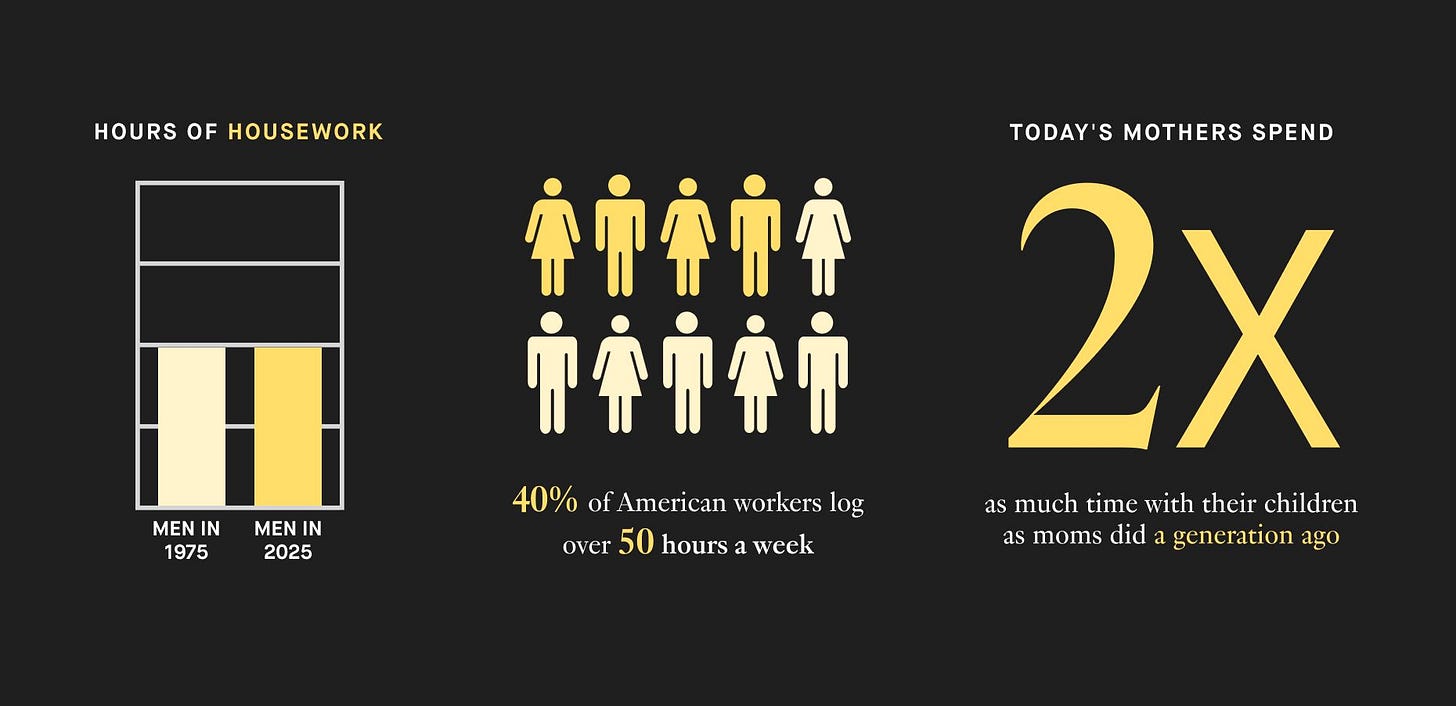

As women have taken on more demanding careers, men’s time doing housework hasn’t budged since 1975. Meanwhile, 40% of American workers now log over 50 hours a week, and today’s mothers spend twice as much time with their children as moms did a generation ago. The math simply doesn’t add up.

Now, Low is touring the country promoting her book, Having It All, an exploration on why that very phrase is a myth—and in the process, she’s living proof that the professional and the personal do not exist in isolation. Last week, I was fortunate enough to grab an hour with her via Zoom as she bounced her four-month-old on her lap. What an apt backdrop for our discussion.

Below read the full interview, and shop the M.M. looks Corinne’s been wearing throughout her book tour.

Having It All by Corinne Low is available now. If you live in Boston, Chicago, or NYC you can catch one of her upcoming book talks at your local M.M.LaFleur store.

You’ve spent your career studying the economics of being a woman. What led you to write Having It All?

“I’m an economist who, throughout my career, has studied the economics of being a woman: fertility timing, the trade-off between career and family, and workplace discrimination. But it wasn’t until 2017, when I gave birth to my son and also had what I’d call a midlife crisis, that I was thrown into the thick of it myself.

I was living in New York, commuting to Philadelphia—two and a half hours each way—and pumping in the Amtrak bathroom. I couldn’t excel or be the person I wanted to be in my work life and family life simultaneously. That’s when my research came to life on a personal level. I wanted to understand why it was so hard, and I found the answer by looking at data. It wasn’t just me—it was the system.”

Why do working women feel like they’re juggling so much in 2025?

“When I looked at the data, it was such an aha moment. Gender roles have converged in the workplace, but they haven’t converged at home. While women have been taking on more and more in their careers, men’s presence in home production tasks has stayed stagnant. Men’s time doing housework, cooking, and cleaning is the same as it was in 1975.

Women are now juggling both domains—stepping into career roles traditionally held by men and trying to perform at the same level, yet we’re still doing so much more at home. What our careers ask of us is also changing. It used to be that a successful career meant a 9-to-5, 40-hour week. Now 40% of American workers work more than 50 hours a week. When you’re trying to give everything to your career while still handling home responsibilities that used to be someone else’s full-time job, it’s easy to feel like you’re falling behind everywhere.”

You also talk about challenges unique to working mothers. What are these?

“The data point that was most freeing for me was learning that moms today spend twice as much time with our kids as moms a generation ago. In the 1980s, when I grew up, there was no extended breastfeeding, baby wearing, or pumping when returning to the office. There was no sitting on the floor with toddlers or elaborate bedtime routines where you process highs and lows and develop socio-emotional skills. In the ‘80s, my bedtime routine was ‘go to bed.’

This change comes from understanding more about child development and how crucial our time inputs are. I think it’s a beautiful, affirmative choice to make these investments in our children, but it’s tremendously costly in terms of our time. When I tell people this—that we’re spending double the time—they’re always surprised. It was very freeing for me because I realized it’s not that I’m failing—the generation before us literally wasn’t doing what we’re doing now.”

What can we do when there’s literally not enough time?

“Once you know the time doesn’t add up, it liberates you to navigate this however works for you by radically prioritizing things that actually contribute to your happiness and well-being, and cutting the rest out. At work, figure out what things actually contribute to your career success in the way you need. I talk about redefining career success—it’s not chasing prestige or salary for the sake of it, but chasing a career that works with your life.

Ask what you’re doing at work that actually contributes to your goals, then say no to ‘office housework’—things people ask you to do that you feel guilty about not doing, but don’t actually advance your objectives.

At home, it means resetting our standards. We cannot be an ‘80s career superwoman and an Instagrammable trad wife simultaneously—those are two separate full-time jobs. I call it ‘throwing out your houseplants.’ Maybe I’m not going to have a garden, and maybe that’s okay, because I’m gardening my career, relationships, social connections, sleep, and physical wellbeing instead.”

Your book has some unconventional advice for women in the workplace. What is it?

“We’ve been given the message that we need to act like men to get ahead—all those book titles that feel like they’re yelling at me: ‘Lean in!’ ‘Stop apologizing!’ ‘Nice girls don’t get the corner office!’ As an economist who studies these issues, I want to tell you there’s actually no evidence that male traits are more productive or that acting like men advances your career.

Take competition research by Muriel Niederle and Lise Vesterlund: they found women tend to be less competitive than men, but everyone forgets the second part of their findings: men over-compete. Even the lowest-scoring men—60% of them—enter tournaments they can’t win. If I’m a manager, I’m more worried about those men taking unwise risks than women who might need encouragement.

In my own research on negotiation, I found that while people rated female negotiators lower than men, there was no evidence they were actually getting less. When I ran my own experiment, women performed just as well against men. But male-male pairs were more than twice as likely to fail to reach an agreement and walk away with nothing compared to pairs with a female negotiator.

What we need to do is advocate for our traits to be compensated fairly. You can always improve your skills, but I don’t want women to change who they are based on messaging that pretends to empower them but actually doesn’t.”

You’re launching this book while walking the walk. Tell me about juggling a book tour with a four-month-old.

“The timing is totally insane, but I’m living the realities of the constraints I discuss in my book. I’m 41, so I didn’t have much time to wait and really wanted a second child. There’s no perfect time to have a child—you do what works for your family and make it work.

Yes, I’m doing a nationwide book tour with a breastfeeding infant at home. I talk about hating pumping all the time, but to maintain breastfeeding while traveling, I’m pumping on planes with ice in my backpack to keep milk cold. Life is crazy. At the same time, my wife got her dream job—full-time in-office with a 45-minute commute—right as I’m launching this book. We’re figuring out logistics like how our son gets to soccer practice, but we’re making it work.”

What does it mean to “think about happiness like an economist?”

“Economics is the science of maximization subject to constraints. Firms maximize profit, individuals maximize something called utility, which is essentially happiness, but richer, because sometimes we do things that don’t feel great in the moment but contribute to long-term goals and wellbeing. Utility is the sum total of our fulfillment, contentment, meaning, and joy over our lifetime.

I ask people: ‘If money were no object, how would you spend your time? What would your life look like?’ That’s what you value. So then you can try to get close to that in a world where you do need to make money. Once you understand your utility function, it becomes your North Star for making choices about what to cut out and what to prioritize.

Only you know what brings you utility and the right mix. You can’t compare yourself to others because you don’t have the same utility function. If someone’s career is progressing faster or they have nicer things, it could be because their utility function is different from yours!”

How does being postpartum affect how you’re dressing for events?

“I was a huge M.M.LaFleur dress fan—one and done. But dresses with high necks and back zippers don’t work for pumping and nursing. I’m doing more separates now, anything that’s a shirt with a skirt or pants, or dresses with lower necklines you can pull down. The Gwynne dress with buttons down the front instead of a back zipper has been perfect for this period.

I’m also dressing for a body that’s still evolving. It took nine months for my body to adapt to house another human, and it takes time to adjust after. You never go back—you’re always postpartum, forever changed by bringing a being into this world, and that’s beautiful. The Colby pants with elastic at the waist fit me at six weeks postpartum and still fit now.”

How are you thinking about professional presentation during this time?

“Early in my career, it was important to look like this image of success I had in my head. My first day at McKinsey, they brought in an old-school speaker who singled out my friend and said, ‘You can’t wear pink pants. No one will take you seriously. Pull your hair back.’ We got the message that we couldn’t show up as our authentic selves.

Now, two kids in, tenured, and in a different place in my career, I have no interest in fitting in. I’m always going to be different—working at a business school as a woman, a person of color, and a queer person. So I want to feel like my authentic self. What looking professional means to me now is: I am a professional, so I want to look like me.”

What makes you feel most confident and authentic in the workplace?

“It took me a long time to figure out my style! Sometimes I only know it by recognizing what I don’t like, like no ruffles, floral patterns, or sequins. I love solid colors in jewel or earth tones, lots of black, and I like mixing in funky accents that feel like me—an elevated earring game and great shoes that stand out against a sleek background.

I love things that are surprising. Recently, I paired M.M.’s crochet dress with a suit jacket. Another combo I love is a feminine dress with combat boots—I’m a ‘90s child and loving the comeback. The Dakota sweater gave me Daria vibes, and I can’t wait to wear it with a skirt and boots this fall.”

Loose Threads

Miscellaneous things that have delighted, inspired, or fascinated the teaMM this week.

The fact that we’ve received nearly 700 responses to our Wear to Work survey.

This heartwarming review of the Moreland blazer: “I was complimented by some fashionable Gen Z coworkers the other week while wearing the Moreland jacket and matching Rina pants. They asked if I could share my secret.”

This 250th birthday celebration, and rewatching Pride & Prejudice to soothe our FOMO.

LOVED this post. Thank you for putting together and sharing.

Back when Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In was the rallying cry for working women, I was in tech as a Sr. Product Manager, balancing a demanding career with life as a new mom. My routine included a 1.5-hour commute each way, four days a week, and weekly day trips to Los Angeles. Like Dr. Corinne Low, I found myself pumping in airport restrooms. On longer work trips, I packed breast milk in dry ice and shipped it home overnight—on my own dime.

The pressure to “lean in” felt relentless, but the truth was that I often wanted to “lay down” (hat tip to Ali Wong). With a career that demanded everything and a baby who needed everything, the math simply didn’t add up.

Today, my infant is nearly an adult, but the equation hasn’t changed for working moms. That’s why Dr. Low’s perspective resonates so deeply with me. As an economist and as a mother, she lays bare what I’ve long felt: “having it all” is a myth, and the numbers prove it.

Her call to radically prioritize, redefine success, and honor our own “utility function” isn’t just refreshing—it’s liberating.